Global warming is on the global agenda. The prospects for business, industry, trade and people’s livelihoods are beginning to be guided by the possible effects of climate change and the options for mitigating it. But it is only in 1999 that awareness of global warming and its consequences began to be talked about openly and everywhere. Here is an account of how the world has been discussing the problem and dealing with it.

“Hockey stick”

The beginning of such a global shift in global climate policy came from a rather short article entitled Northern Hemisphere temperatures over the last thousand years: findings, uncertainties and limitations by University of Massachusetts climate scientists Michael Mann, Raymond Bradley and Malcolm Hughes of the University of Arizona. The paper was published in the American Geophysical Union (AGU) journal Geophysical Research Letters in 1999. Scientists have identified the rise in global temperatures over the past 1,000 years by recording temperature measurements from 1902 to 1998 and studying tree rings, coral reefs, layers of ice and literary data that have documented the planet’s conditions over the centuries. To validate the conclusions about temperature variations prior to 1902, scientists conducted studies of natural data, which showed that the method produced similarly accurate results as temperature records.

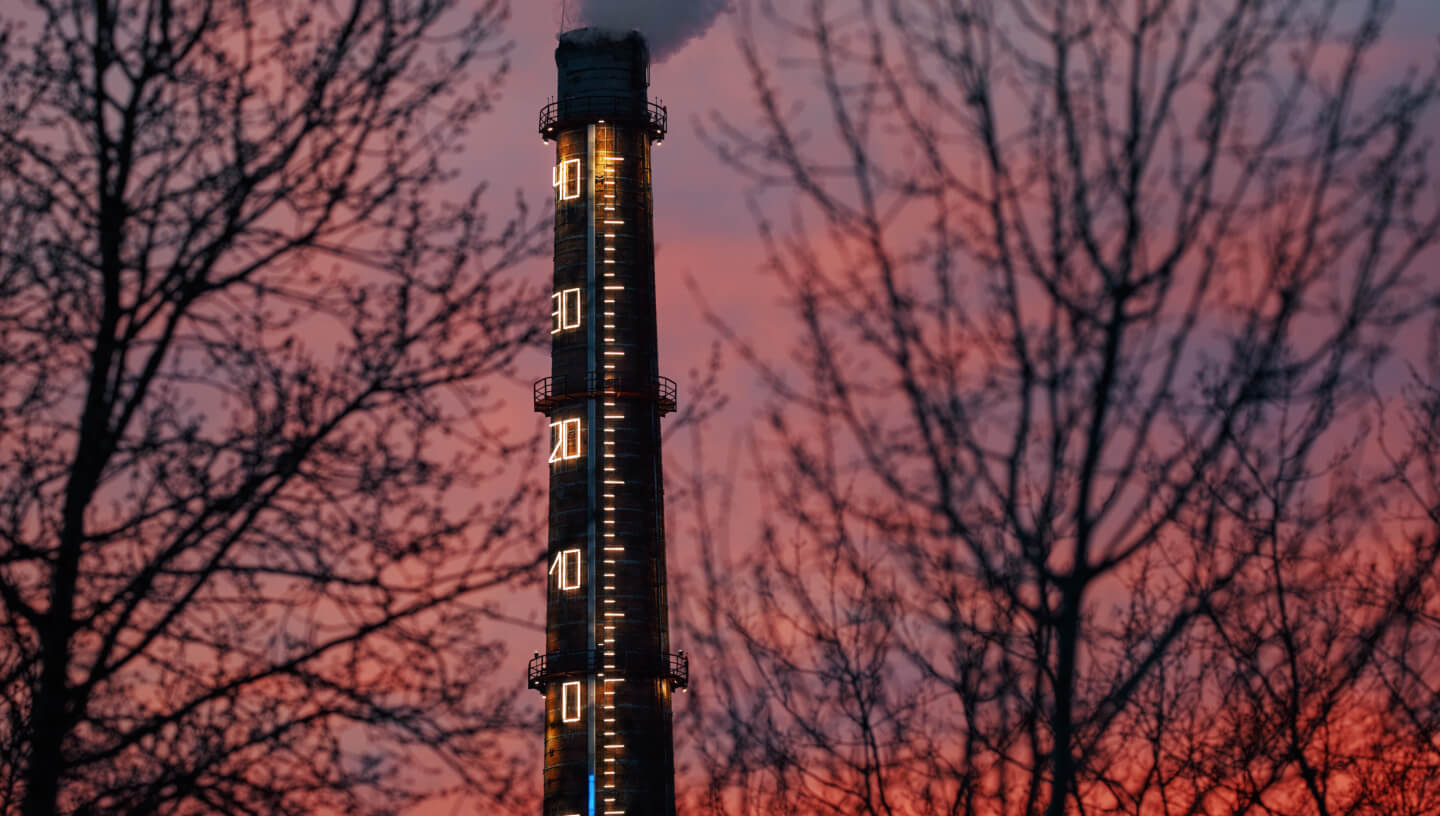

Data on global temperature change is shown in a graph called the Hockey stick graph. It shows that until the beginning of the twentieth century the global temperature remained at an average of minus 0.3 °C of the accepted norm. A noticeable cooling was observed in the middle of the 14th and the middle of the 15th centuries. Since the beginning of the twentieth century, the temperature increase has continued apace, with an average rise of more than 1 °C in 100 years.

Photo by: Veronika Saratovtseva / iStock

Photo by: Veronika Saratovtseva / iStock

What happened before

The first studies on possible global warming appeared at the end of the 19th century. Swedish scientist Svante Arrhenius was the first to raise the issue of the negative impact of greenhouse gas on nature on a global scale. Then, in the early 1960s, scientists at the Mauna Loa Observatory in Hawaii, led by climate scientist Charles Keeling, first scientifically proved that the concentration of CO2 in the Earth’s atmosphere was increasing every year. Their conclusions were based on observations of the atmosphere since 1958. And the graph of changes in CO2 levels in the atmosphere that has existed since then is called the Keeling Graph.

In the mid-1980s, in addition to black carbon, other substances associated with anthropogenic emissions, such as methane and nitrogen oxides, became known to have a negative impact on the climate. The ozone hole over Antarctica was ‘discovered’ and this added weight to the growing alarm.

However, until the end of the twentieth century, the topic of anthropogenic harm to the atmosphere and the dangers of global warming was confined to the scientific debate and did not reach the political level. In 1979, the First World Climate Conference was organised, the organisers of which tried to involve politicians in the discussions, but without success. In the late 1980s, major events devoted to global warming, attended by the political elite, gradually started to take place. These included a major climate change workshop in Fillach, Austria, in 1985, the Toronto conference in 1988 and later in The Hague and Nordwijk in 1989. In the late 1980s, the issue of global warming was repeatedly raised in the US Congress and at the UN General Assembly, but no concrete action was taken by governments.

The dilemma: ecology and politics

In December 1988, a resolution of the UN General Assembly recognised the problem of global warming as a universal issue requiring global attention. This statement drew many governments from around the world, mainly from the developed world, into the discussion. The Nordwijk meeting brought together representatives from 17 countries to discuss first of all the question: what to do about greenhouse gas emissions and how to reduce them. During the negotiations, there was a split between two camps of governments: the so-called CANZ group (Canada, Australia, New Zealand) proposed to follow the experience of acid rain, i.e. to limit emissions by reducing production by regulating its targets and timing. This was opposed by the USA, as well as by the USSR and Japan, arguing that this approach was unrealistic because the goals and timing of production cannot be controlled so globally, especially without taking into account national needs and circumstances.

The US insisted on further study of the problem, and the idea of creating and implementing national programmes to reduce emissions was also voiced. Here, it is worth noting that the USA produced electricity in a very polluting way (and this method is still used today) — by burning coal. It was not profitable to abandon this practice, and there were no alternatives at the time. In Europe, Germany was the main sponsor of coal production, but like other European countries, it had the option of switching to a cleaner fuel — natural gas — by buying it from the USSR. Such a deal could have disrupted US political parity and changed the balance of power in the world, which did not suit the United States government. Apparently, it was big politics that caused controversy over environmental issues and delayed the resolution of the underlying problem.

Photo by: Tas3 / iStock

Photo by: Tas3 / iStock

Consensus of scientists and governments

A serious dialogue between climate scientists and governments began after the 1988 Toronto Conference and did not emerge until 1990. By then, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) was created at the initiative of the World Meteorological Organisation (WMO) and the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). In 1990, the IPCC released its first report on global warming. It stated the problem of the greenhouse effect through emissions of carbon dioxide, methane, chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and nitrogen oxide. The scenario of global warming due to emissions was grim: global temperatures were expected to rise by an average of 0.3 degrees per decade and by the end of the 21st century to be 4 degrees higher than in the pre-industrial period. In addition, due to differences in the economic development of each individual country (e.g. expressed in output or trade policies), warming may occur unevenly. The lack of comprehensive data on greenhouse gas emissions and the need to study this issue in more detail was also recognised.

The detailed analysis of the current environmental situation and projections outlined in the report (concerning the impact of global warming on glaciers, oceans, land, the immediate human environment) impressed both the scientific community and political circles. Negotiations between scientists and politicians on real action began after the report was released. Here, too, key points of concrete action were identified: the need for funding and the introduction of legislative measures.

In 1992, the United Nations Conference on Environment and Development was held in Rio de Janeiro, which resulted in the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, signed by 192 countries. The aim of the convention was to develop a common agreement for all to take joint action to combat global warming. The convention resulted in the Kyoto Protocol, signed by its member countries in 1997. The Kyoto Protocol set out the basic principles for combating global warming by reducing greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere to “a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system”. The Kyoto Protocol was built around the control of seven greenhouse gases listed in Annex A: carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (N2O), hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), perfluorocarbons (PFCs), sulphur hexafluoride (SF6) and nitrogen trifluoride (NF3). The Treaty did not enter into force until 2005.

To be sure, the Kyoto Protocol reflected considerable progress in the dialogue between scientists and governments. Still, a single united struggle based on it did not happen: the US never ratified the treaty, and Canada withdrew in 2012. Nevertheless, until 1999, the global warming debate was conducted in a rather closed format, with little public discussion.

Debates, controversy and sad conclusions

Since the Mann, Bradley and Hughes article appeared in print, there has been open discussion, first among scientists and soon on a political and public level, about the causes of global warming. In fact, there were two options: either it was a natural process, or anthropogenic factors contributed to it. By that time ideas for sustainable development and reducing waste and production emissions for the sake of the environment had been floating around for decades. However, despite research and activities on global warming in the 1980s and 1990s, many scientists have long been reluctant to believe in the obviousness that human activity has caused such severe damage to nature.

The opponents argued that there is certainly global warming, but that the cause is not a human factor, but natural earth processes. The article “Temperatures in the northern hemisphere...” was criticised. In particular, the inability of humans to influence nature on such a large scale was recognised as another argument, despite the fact that emissions of anthropogenic origin have indeed increased in recent decades.

Photo by: SeppFriedhuber / iStock

Photo by: SeppFriedhuber / iStock

Is global warming a pattern?

Even from school textbooks we know that global climate changes such as glaciation (ice ages) or warming are natural processes on the planet and that the seemingly noticeable increase in average temperatures in recent decades could well be a normal, natural stage in the life of the Earth.

In the 1920s, Serbian scientist Milutin Milankovic created his own theory about the changing of climatic epochs on the planet, now known as Milankovic cycles. He concluded that climate changes depend on variations in the amount of sunlight and solar radiation reaching the Earth, depending on changes in the position of the Earth’s axis and its orbit. Milankovic’s theory proves the regularity of previous global climate changes. If this is correct, can we assume that the current global warming is also natural and logic?

Still no: hard science vs hypotheses

Additional research soon yielded ample evidence that the Hockey Stick authors were right. A counter-criticism refuted the claims of natural warming: global climate processes have occurred gradually over millions of years, millennia or at least several centuries, but not in a matter of years. Moreover, according to Milankovitch cycles, the twentieth century was supposed to be a period of relative cooling within the warm Holocene (interglacial) period, in which the Earth has been in for 12,000 years. It is known that the warmth peak of the Holocene lasted from about 9 thousand to 5 thousand years B.C., after which a slow general cooling began.

In 2001 the IPCC issued a third report on global warming, declaring anthropogenic causes of temperature rise to be paramount. It noted that since the mid-twentieth century there is a 66% probability of human influence on the rate of global warming. It was stated that the rate of warming in the twenty-first century could accelerate if no mitigating measures were taken.

Of course, it could be said that the findings of the Mann, Bradley and Hughes article were not entirely new to the scientific community, given the numerous studies and papers of the previous two decades. However, it was this article that got the whole world talking about global warming and significantly influenced changes in countermeasures policy.

A new plan

In 2015, a conference was held in Paris under the auspices of the UN Framework Convention. It was attended by representatives from 195 countries and resulted in the Paris Agreement on Climate Change, which aims to reduce carbon dioxide in the atmosphere from 2020. This document replaced the Kyoto Protocol and, in contrast, introduced a major change in policy to address the problem. Member countries of the agreement have committed to individual programmes to reduce CO2 emissions in order to reduce the rate of global warming from 2 °C to 1.5 °C in the coming decades.

The Paris Agreement was supposed to lead to individual programmes within five years and their implementation from 2020. In reality, the agreement has also led to the emergence of individual sustainability programmes for many of the world’s largest manufacturing concerns and private companies. These programmes are in line with the Paris Agreement’s main objectives: reducing greenhouse gas emissions, controlling industrial waste and eliminating natural disasters due to emissions.

In Russia, sustainable development programmes have been adopted by all major companies in the energy, metals, mining and consumer product sectors.

Author: Ekaterina Lidskaya

Cover photo: Gallo Images / Getty Images

Comments